Shall I refer thee to all those lawsuits about fair use? Researchers think this result makes them worth revisiting

Readers of texts created to use the styles of famous authors prefer works written by AI to human-written imitations, but only after developers fine-tune AI models to understand an author’s output.

This finding, academics argue, means the courts need to rethink assumptions about allowing AI training on authors' works as a fair use exception to copyright liability.

In a preprint paper titled "Readers Prefer Outputs of AI Trained on Copyrighted Books over Expert Human Writers," Tuhin Chakrabarty, assistant professor of computer science at Stony Brook University, Jane C. Ginsburg, professor of law at Columbia University, and Paramveer Dhillon, associate professor in the School of Information at the University of Michigan, describe how they assessed the impact of AI models that can emulate the style of human writers.

They chose to do so in light of the various lawsuits filed on behalf of authors who claim developers of AI models unlawfully used their works for training. One such lawsuit, Bartz v. Anthropic, is expected to settle for $1.5 billion after Anthropic trained its models on copied works.

In another such lawsuit, Kadrey v. Meta, Meta prevailed on a technical basis – due to legal deficiencies in the plaintiffs' case – even as the judge acknowledged "that in many circumstances it will be illegal to copy copyright-protected works to train generative AI models without permission."

Copyright holders have filed More than 50 copyright lawsuits against AI companies in the US alone, a list that includes claims based on video and audio reproduction. Legal scholars have suggested that while training AI models on copyrighted texts, recordings, and videos is probably permissible as fair use, there's likely to be liability for AI models that produce copyrighted content verbatim.

But if AI training itself becomes a legal risk, the AI model makers could face ruinous costs – on top of the billions already bet on data centers to satisfy hoped-for AI demand. Former Meta executive Nick Clegg recently opined that having to ask artists for permission to scrape their work will "basically kill the AI industry in this country overnight."

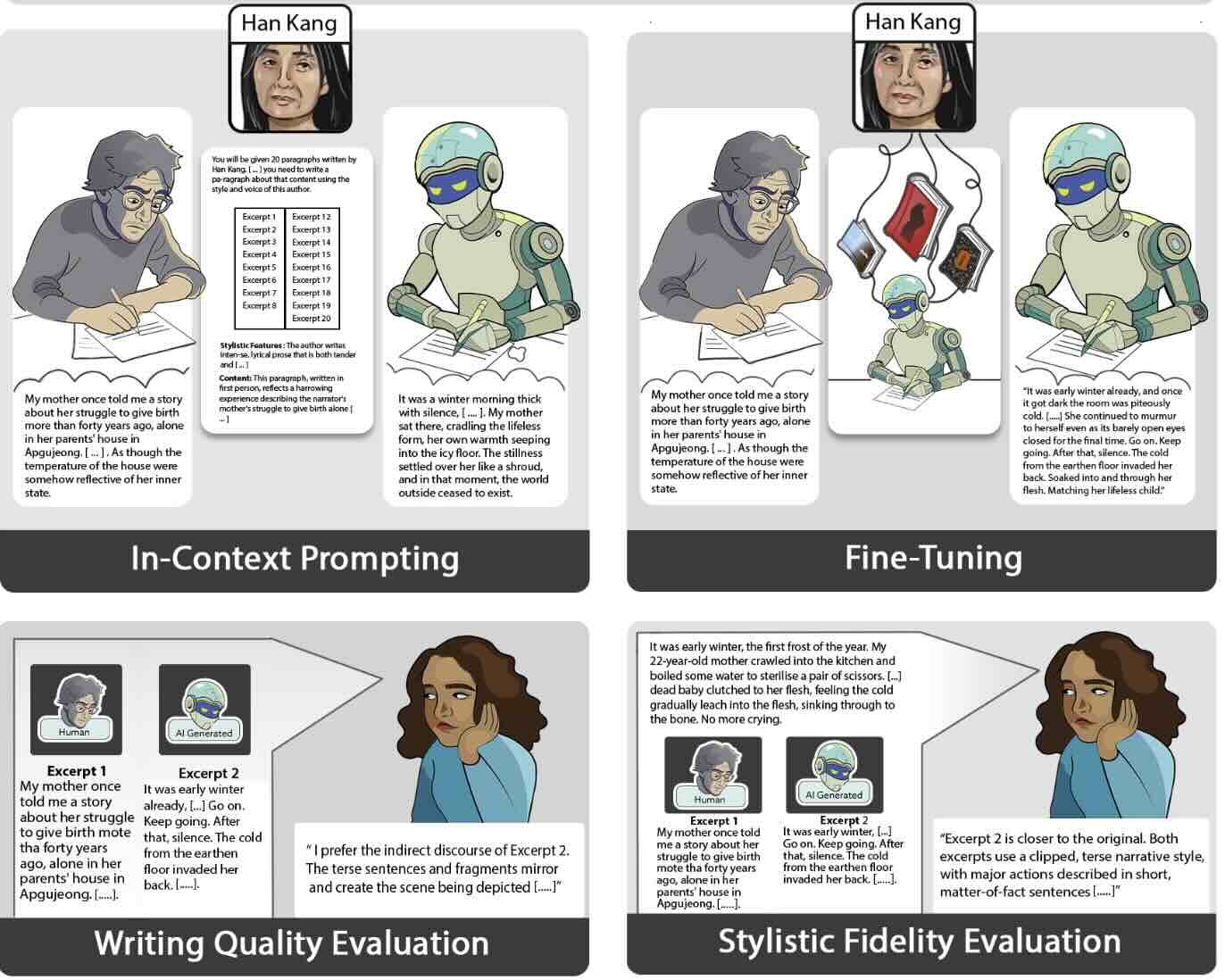

Chakrabarty, Ginsburg, and Dhillon set out to determine whether AI models can generate high quality literary text that emulates an author's specific writing style.

"Past research has shown that AI cannot produce highbrow literary fiction or creative nonfiction through prompting alone when compared to professionally trained writers," they state in their paper.

The authors of the paper therefore recruited 28 candidates from top Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) writing programs and asked them to produce 450-word excerpts in the style of 50 award-winning authors. The researchers compared the resulting 150 human-written excerpts – imitations of the works of Alice Munro, Cormac McCarthy, Han Kang and other literary VIPs – to 150 AI-generated excerpts that also tried to match the styles of famous authors.

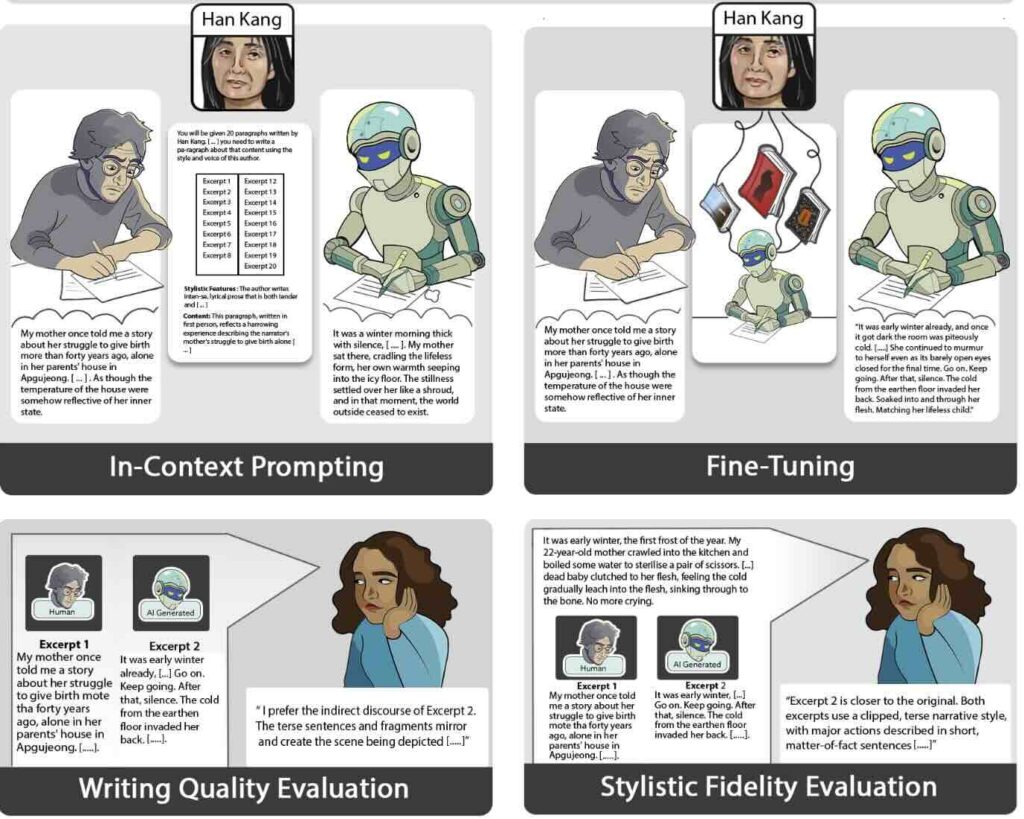

28 MFA expert writers and 131 lay readers preferred human-written works. But that changed after developers fine-tuned the models used to create the imitation texts – rebutting past research showing that AI can't generate what people consider to be great literature.

"In blind pairwise evaluations by 159 representative expert (MFA candidates from top US writing programs) and lay readers (recruited via Prolific), AI-generated text from in-context prompting was strongly disfavored by experts for both stylistic fidelity but showed mixed results with lay readers," the authors state in their paper.

"However, fine-tuning ChatGPT on individual authors’ complete works completely reversed these findings: experts now favored AI-generated text for stylistic fidelity and writing quality, with lay readers showing similar shifts."

The fine-tuning process, the authors observe, appears to remove detectable AI stylistic quirks, like cliché density, that human readers dislike.

Dhillon told The Register he's unable to provide a quotable response to The Register's questions because the journal where the paper is under review forbids interviews with journalists prior to publication.

But generally he said that reader preference for AI-generated text over human writing in blind evaluations, when considered in the context of the low production cost of AI-generated text, means that AI literary works could compete with, and even displace, human-authored works.

In other words, it appears legal types cannot now ignore the market impact of AI upon human-authored works when assessing whether AI's use of copyrighted content is fair.

Defendants accused of stealing copyrighted material can invoke a fair use defense in the US based on a four-factor test. Judges must consider: the purpose and character of the use (e.g. commercial, non-commercial etc.); the nature of the copyrighted work (factual works would be less likely to be protected than fictional ones); the amount of the work copied; and the "effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work."

The authors calculate that the median cost of fine-tuning a model and performing inference to produce a 100,000 word novel amounts to $81, representing a 99.7 percent reduction in what it could cost to hire a professional writer ($25,000) to create that work.

"These findings suggest that the creation of fine-tuned LLMs consisting of the collected copyrighted works (or a substantial number) of individual authors should not be fair use if the LLM is used to create outputs that emulate the author's works," the authors of this paper conclude.

Anticipating that legal scholars might dismiss their findings because AI models in this scenario are not producing verbatim copies of published works, the authors counter: "The Copyright Office's expansive interpretation of 'potential market for or value of the copied work' suggests that fair use might not excuse predicate copying even when it doesn't show up in the end product, if the copying's effect substitutes for source works."

Shortly after that report surfaced in May, President Trump fired Shira Perlmutter, Register of Copyrights, "less than a day after she refused to rubber-stamp Elon Musk's efforts to mine troves of copyrighted works to train AI models," as Rep. Joe Morelle (NY-25), put it. ®

Source: https://www.theregister.com/2025/10/21/ai_wins_imitation_game_readers/