The music industry must plan for the day when AI music-generation tools produce humanlike music in bulk.

Indie rock band The Velvet Sundown amassed millions of streams on Spotify until it was revealed that the ‘band’ is not real and its music is AI-generated — as are all images of the band © The Velvet Sundown

The internet is drowning in slop. From trampoline-jumping bunnies to “shrimp Jesus” — a bizarre genre that melds religious images with the body of crustaceans — social media feeds abound with mindless text, videos and images generated by artificial intelligence. But cover your ears, because the same might soon be true for music playlists.

Spotify, which claims about 700mn monthly active users, said it was forced to remove 75mn “spammy” AI-generated tracks from its platform amid a surge over the past 12 months. At French streaming service Deezer, over 28 per cent of the tracks uploaded to its platform each day are generated by AI, up from just 10 per cent in January.

This marks an evolution in the ways in which technology is affecting the music industry. In the past, it was used to cheat the streaming algorithms. Scammers would upload a small number of tracks to music platforms and have automated bots play the content repeatedly to generate royalty payments. But this was easy to detect.

Now, however, AI is starting to generate content that is difficult to distinguish from that of human artists. Indie rock band The Velvet Sundown amassed millions of streams on Spotify until it was revealed that the “band” is not real and its music is AI-generated.

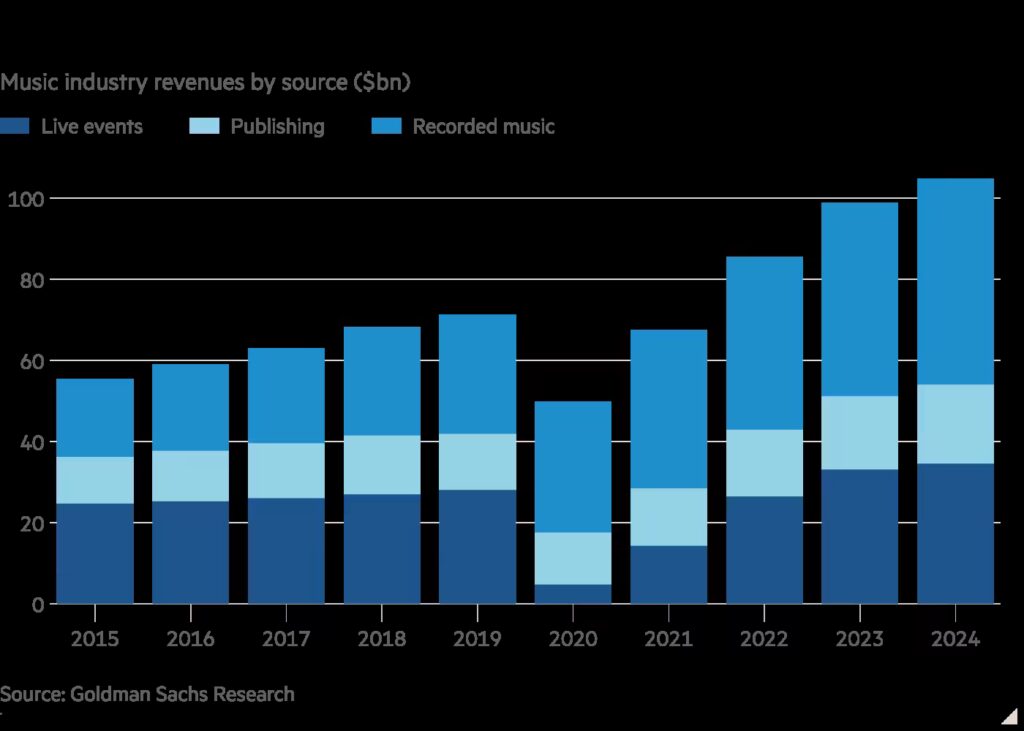

This raises a number of concerns for the $105bn music industry. One is outright fraud: presenting tracks as authentic creations of an artist when they are anything but. ChatGPT-style AI song generation tools such as Suno and Udio enable anyone to make a Taylor Swift-style song with a few keystrokes. There, at least, copyright infringement laws may provide plausible protection.

A more complex issue is what happens when AI music-generation tools, trained on millions of human tracks, produce humanlike music in bulk. That’s not so bad for streaming platforms — they are incentivised to maximise playing time, and are less concerned about who’s being listened to. But it may well marginalise existing music companies and human artists, especially where content is not particularly original, or where the fan community is less engaged.

The music industry will need to be proactive. Labels may try to create their own AI artists. Meanwhile, for their human assets, live events and concerts will become even more important; these already made up about a third of the global music industry revenue last year, according to Goldman Sachs analysis.

Most of all, they will need to reach a truce with AI companies — say, allowing them to have access to music for training purposes in return for a licensing fee, or somehow producing payments whenever AI generated content riffs off their back catalogues. Universal Music and Warner Music are reportedly considering such deals already. The question isn’t whether they strike a deal over their artists’ work, but whether they can avoid selling it for a song.

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/f1dfc2f5-9e4d-4f0a-8008-cdc87bd1cef9