The battle over how AI is built — and who gets paid along the way — must be resolved to benefit both art and technology.

The AI sector is very good at taking. Can it learn to give? Illustration: Simon Landrein for Bloomberg Opinion

Björn Ulvaeus, the legendary songwriter and one-quarter of the famed Swedish pop group ABBA, is staunchly pro-artificial intelligence. “It's like an extension of my mind,” he says. “To be a Luddite in this is just crazy. It is here.”

Ulvaeus is using AI tools to help him write a new musical. He has used them to simulate how his new work might sound with different styles of vocalists or when played by an orchestra, refining his compositions based on the results. “It will take recorded music in new directions,” he says.

That’s music, literally, to the ears of those who build and market these tools. But where Ulvaeus differs from many other AI enthusiasts is his stance on how these technologies should be built and who deserves to get paid along the way.

“You cannot avoid the fact that its sheer existence is because of the songs that I wrote in the past,” he tells me. “I should be remunerated for that. If you make money on something that I helped you create, I get a share.”

Whether creatives like Ulvaeus are entitled to any payment from AI companies is one of the sector’s most pressing and consequential questions. It’s being asked not just by Ulvaeus and fellow musicians including Elton John, Dua Lipa and Paul McCartney, but also by authors, artists, filmmakers, journalists and any number of others whose work has been fed into the models that power generative AI — tools that are now valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Building generative AI models, whether for outputting text, audio or video, requires staggering amounts of training material. Meta Platforms Inc.’s most recent model, Llama 4 Scout, was trained on a corpus of data equivalent to more than 300 million 300-page books.

To feed these models, companies have looked for the highest-quality data — i.e., the kind produced by human creativity and ingenuity. That includes resources like Library Genesis, or LibGen, a collection of more than 7.5 million books and 81 million academic research papers; Books3, a database of 191,000 fiction and nonfiction works chosen for their “invaluable” role in demonstrating “coherent storytelling”; and more than 15 million YouTube videos.

They are pumping all of this — and much, much more — into their AI systems without paying a dime to those whose work is contained within the many petabytes. It is, as described by the Republican senator Josh Hawley, “the largest intellectual property theft in American history.”

The companies involved — the datasets outlined above are referenced in lawsuits against OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta and others — all maintain they have acted legally, citing the fair use doctrine. The legal framework says that copyrighted material can be used without permission or payment if, among some other criteria, the end result is sufficiently “transformative.” AI companies have argued that what their creations spit out qualifies. In most cases, the authors, researchers, artists and content creators whose work was used disagree. So far, judges have been split.

Throughout US history, new technologies have repeatedly tested copyright law. But the scale of this challenge is unique, with stakes that are economic as well as cultural. The International Intellectual Property Alliance, a trade association, estimates that core copyright industries — that is, industries with the primary purpose of creating and sharing copyrighted materials — accounted for 8% of US gross domestic product in 2023, supporting just under 12 million jobs.

While creative work comes from around the globe, solving this problem will fall to the US. The majority of the leading AI giants are based here, as are the bulk of the creative and scientific industries involved. And perhaps most crucially, our democracy offers the best shot at creating — and enforcing — a solution. That’s because, while the US tech industry has the ability to build a technical fix, it will need the help of Congress for those solutions to get any real purchase.

Time is of the essence. AI models that pilfer the work of human thinkers and creators without payment — then offer the public an ersatz version of what they create — undermine their livelihoods. At a moment when industries like Hollywood and publishing are already struggling, some worry it could be a fatal blow.

Ironically, that’s also a threat to the future of artificial intelligence itself. Failing to resolve the copyright conundrum in a way that works for all involved could be a “real problem” for innovation, warns Tom Gruber, inventor of the Siri AI assistant. “You’ll have nothing authentic to train on anymore.”

AI’s champions speak of its development in the same determined tones as the race to the moon or the building of the atom bomb: with warnings of devastating consequences if the ambition is realized too slowly. For this reason, many AI companies and their investors maintain that paying content creators for their work is neither warranted nor practical. As venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz put it starkly in its submission to a US Copyright Office report: “There is a very real risk that the overzealous enforcement of copyright when it comes to AI training” could “cost the United States the battle for global AI dominance.”

But what constitutes “overzealous” — and who gets to decide? Another criterion of the fair use test is that the market for a copyright holder’s work is not harmed. Some industries say this harm is already being done. News outlets say Google’s AI Overviews, which synthesize content into a single answer within Google Search, have caused a plunge in readership. Fewer clicks equals fewer ad dollars, which are still the lifeblood of many publications. Penske Media Corp., publisher of Rolling Stone, is suing, saying AI Overviews has “profoundly harmful effects on the overall quality and quantity of the information accessible on the internet.”

Most agreed that AI companies should compensate publishers when using their work to train large language models

Source: News/Media Alliance poll, April 2024

Note: Online survey of 1,800 registered US voters. The News/Media Alliance is a trade association representing more than 2,000 news, magazines and digital media businesses

A first-of-its-kind study conducted by the Paris-based International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers offers some bracing predictions about the impact AI-generated music and visual media will have on the market for human artists. The nonprofit represents more than 5 million creators, including Ulvaeus, who is also its president. The study forecasts that musicians risk losing 24% of their revenues by 2028, while those in audiovisual industries could see a fall of 21%.

Proponents of AI push back on these kinds of figures, saying that AI-generated content is additive, and that the appetite for human-made work will remain healthy. But there are already troubling signs to the contrary: The streaming platform Deezer reported that 28% of the music submitted to it in June this year was AI-generated — up from 10% in January. Emerging artists say this flooding of the market makes it harder for new human performers to break out.

Hollywood’s talent pipeline is also suffering. Sam Tung is an LA-based storyboard artist whose clients have included Marvel, A24, Nintendo and Warner Bros. He also co-chairs the AI Committee of the Animation Guild, an organization born in the aftermath of Walt Disney’s efforts in the 1950s to ship some of his cartoonists’ labor overseas. Members worry that entry-level gigs are disappearing, says Tung. At the same time, established professionals are reporting demands that projects be kept shorter and cheaper, as more clients suggest the work can be streamlined using AI.

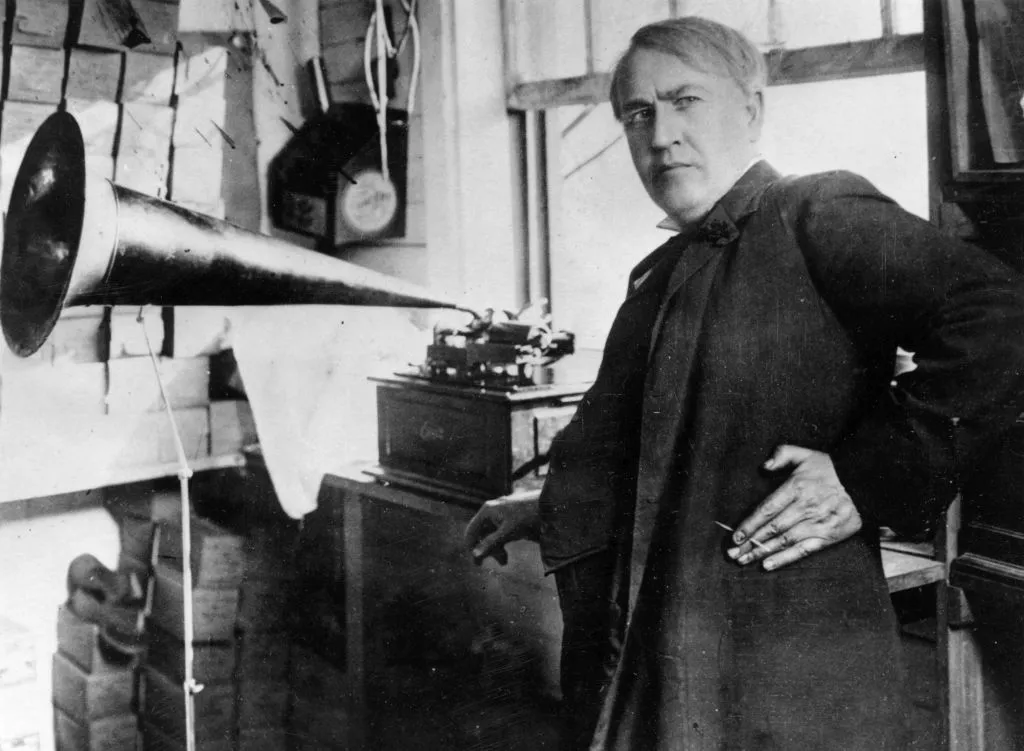

In the past, disruptive technology has often been the catalyst for sensible copyright reform. In 1906, at the urging of President Theodore Roosevelt, two congressional committees convened with the task of updating the Copyright Act in the wake of new so-called talking machines — what we’d recognize today as gramophones. Renowned composer John Philip Sousa told the committees that it was unfair that the equipment manufacturers were profiting off phonograph sales without compensating those who wrote or performed the music. “They have to buy the brass that they make their funnels out of, and they have to buy the wood that they make the box out of, and the material for the disk,” he said. “That disk as it stands, without the composition of an American composer on it, is not worth a penny.”

By 1909, the law had been updated to make sure musicians could benefit from collective rights, blanket agreements that avoid the need to negotiate with every party looking to use a copyrighted work. The decision was greeted by howls from equipment manufacturers, one of whom said in the same hearing that companies “will be put out of business, and their workmen will have their field of labor and bread taken away.” Instead, the modern recorded music industry emerged and flourished.

The parallels with today’s “talking machines” — AI chatbots like ChatGPT — are uncanny. This year, research group Gartner estimates, companies and investors will pour some $1.5 trillion into AI. It predicts $2 trillion by next year. To channel the spirit of Sousa: AI companies pay for the data centers they build, the power to run them and engineers to write code. So why not pay for the work of human creators, without whom today’s AI models wouldn’t be worth a penny?

Forecasts predict that next year's investment will double what was spent in 2024.

Source: Gartner

There have been some content deals between publishers and AI companies, such as OpenAI’s five-year deal with the publisher of the Wall Street Journal. But the motivation to enter such agreements will likely evaporate if the courts decide they’re unnecessary.

In June, U.S. District Court Judge William Alsup, ruling in California in the case of several book authors suing Anthropic, said that from a legal perspective, the AI training process is similar to “training schoolchildren to write well.” He added: “This is not the kind of competitive or creative displacement that concerns the Copyright Act.”

Alsup’s comment is the clearest evidence yet that judges have been left unarmed when dealing with the modern talking machine. We have a copyright law that does not address the difference between a thinking human and a “thinking” computer, because it was conceived at a time when the latter was science fiction.

In May, the US Copyright Office weighed in, concluding that the fair use defense was far from blanket, and recommending “effective licensing options” that would simplify the process of paying creators for their work in a manner that sustained both the technology and the creative industries.

A suitable system, it said, would have the effect of “reducing what might otherwise be thousands or even millions of transactions to a manageable number.” This model exists today in other applications. Think of a local radio station: Rather than broker a separate deal with every musician it wants to play on the air, it strikes a single agreement with collecting societies, such as the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. ASCAP handles the distribution of royalties among its million-plus members.

This music rights model was the direct inspiration for Really Simple Licensing, a new standard that lets publishers add code to their websites to set granular rules on how the content can be used and paid for. A consortium that includes Reddit Inc., Yahoo Inc., O’Reilly Media Inc. and Ziff Davis Inc. is backing the initiative. WordPress, the most widely used web publishing platform, has already implemented it for its users.

“We're not reinventing the wheel here,” says Doug Leeds, co-creator of RSL. “We're taking a wheel that already works really well and we’re just attaching it to our industry.”

The consortium argues for payment at both ends — a fee for use in training data, as well as an ongoing fee when information is used in answers. This aim is shared by Pasadena, California-based startup ProRata.AI, which says its technology can deconstruct AI answers to determine the originating source. Its chief executive is Bill Gross, inventor of the “pay-per-click” advertising model that powers most of the web economy. He calls the process “unscrambling the egg.” “If your content is used in lots of answers, you should get a big royalty check,” Gross says.

Another has come from Cloudflare Inc., a company known colloquially as the “nightclub bouncer” of the web; its systems analyze incoming web traffic to prevent cyberattacks or overloading. That same firewall can also be used to stop AI scrapers at the door — unless a publisher chooses to allow it.

“If we can separate robots from humans technically, then it's not clear that we actually need changes in any regulatory regime,” argues Cloudflare Chief Executive Officer Matthew Prince. The Copyright Office agrees with him, saying the market might solve the issue before any congressional action is needed.

But while these technical approaches make it possible for content creators to be paid with minimal friction to the task of gathering data for AI models, they share a fatal weakness: AI companies are under no obligation to engage with them. For any of these approaches to gain traction, US lawmakers must step in and require that companies comply.

Failing to do so would set the conditions for weakening copyright protections globally. In the UK, for instance, lawmakers are seeking to loosen historically strict copyright laws “in order to essentially attract AI companies and not ‘miss out on AI,’” warns Ed Newton-Rex, a composer who resigned as head of audio at Stability AI in protest over the company’s embrace of fair use for training models.

Complicating the situation, any US protections would need to happen without the backing of the Trump administration. The EU’s efforts to implement stricter rules on AI training data have been met with derision from the White House. At an AI summit in Paris in February, Vice President JD Vance called out European leaders on safety regulations that would “strangle” innovation in AI.

President Donald Trump seems similarly unmoved. “You can't be expected to have a successful AI program when every single article, book, or anything else that you've read or studied, you're supposed to pay for,” he said at the launch of his AI Action Plan, which contains no protections for creators’ rights. “‘Gee, I read a book,” he joked. “I’m supposed to pay somebody.”

Congress should look past such comments and act fast. The low-hanging fruit is transparency. In 2020, when detailing its new GPT-3 model, OpenAI made clear which databases of copyrighted books and Wikipedia entries it had used. By 2025, such disclosures had disappeared, ostensibly to protect a trade secret, but ultimately, it seems clear, to reduce the possibility of copyright lawsuits.

The EU’s AI Act requires builders of general-purpose AI to publish a “sufficiently detailed summary” of training data by August 2027 — or face fines of up to €35 million or 7% of global revenue, whichever is greater. The US should adopt similar rules. As well as making rights holders aware when their material has been lifted, it’s a safety no-brainer: We should know what data is being fed into machines that will be used to help teach children, hire new employees and make medical decisions.

Next, those in the business of creating content should have access to collecting societies that can license content quickly and at scale — and AI companies should have a legal obligation to use them. Far from slowing progress, such systems could have significant positives for the tech industry, especially if these societies can adhere to uniformity on how data is shared with AI companies, negating the need for messy and expensive web scraping.

Collective licensing should take preference over a fragmented system, such as one proposed by OpenAI, which would require copyright holders to proactively tell each AI company not to use their material. Content providers should also have the option to opt out of all models at once.

Finally, the fair use doctrine must be updated to reflect that the nature of “fair” changes profoundly when a machine, not a human being, is doing the “work.” A reformed law should disqualify AI training from fair use protections, with exemptions for narrow and noncommercial purposes. Removing the ambiguity left by lawmakers who couldn’t predict the future is the best way to protect content creators in the long term.

Copyright reform might seem an impossibility when pitted against the ambitions and wealth of the AI industry, as well as a presidential administration with no interest in the topic. No efforts to introduce federal legislation on this issue have yet made it to a vote in Congress. To move forward, the debate must be recast, making it clear that protecting creative industries will help sustain the flow of quality information into the AI models of the future. Otherwise, the industry faces the scenario Siri creator Gruber described, known as “model collapse” — where AI models train solely on AI-created materials, slowly degrading over time.

Put simply, paying creators to keep creating is about as pro-AI and pro-innovation as it gets.

Such controls would begin to maintain copyright law’s historical purpose, reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in 1985, as the “engine of free expression.” Far from holding the US back in the AI race, protecting these rights will give homegrown AI companies a winnable edge: a thriving creative industry that produces world-beating works for years to come.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/features/2025-10-14/ai-s-copyright-war-with-dua-lipa-elton-john-could-be-its-undoing